Singapore's HEAVILY Subsidised Universities.

-

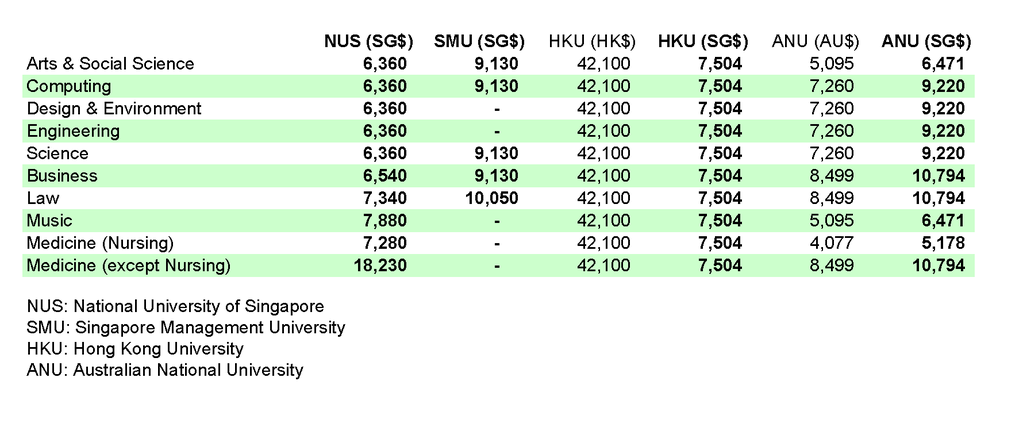

The P4P government always claim that our education system is "heavily subsidised",

so I took it upon me to find out exactly how heavily subsidised it is compared to

citizens of other similar countries.

But it seems like the cost of tuition in Singapore and the cost of tuition paid by citizens

in another comparable country is almost the same.

I think that the P4P government should stop referring to education as "heavily subsidised", it makes

it seemed as if they paid up to 95% of your cost of tuition and the students are beholden to them.

The education system afforded by the P4P government to her citizens when compared to other

countries could at best be called "subsidised" and not "heavily subsidised"

Perhaps their idea of "heavily subsidised" is to increase the price of tuition fees, then mark it down

to what the price of tuition fees should be and declare that has "heavily subsidised" (akin to our HDB flat prices).

Source: https://team.nus.edu.sg/registrar/info/ug/UGTuition2008-9(Cohort).pdf

Source: http://www.hku.hk/acad/ugp/finance_fee.html

-

mmm

i should point out to the less observent reader that the stats quoted there come from OTHER subsidised universities. Do you want me to show you MY university bill from australia?

So what's your point? That the Sg gov is subsidising as well as the other countries are?

Just because other countries subsidise as much as SG does not mean it's not heavily subsidised. What, it's a race now? Do we mark along the bell curve now?

-

I do wish that the P4P government refrain from using the term "heavily subsidised", heavily subsidised relative to

which country? Countries in the region or Timbuktu or Antartica?

Seems that other countries give a similar amount or even more subsidy, therefore it is just a subsidy, not a heavy subsidy.

You are talking about your university bill as a "non-citizen" in Australia as compared to the university fees paid by "citizens" in Singapore?

Is that a fair comparison coming from someone who has some form of tertiary education?

Has your course anything to do with flower arrangement or casket services?

It sure doesn't reveal any signs that your course has anything remotely linked to logic and thinking.

You logic is amusing.

-

whats subsideised mean?

-

Whether something is heavy or light, there needs to be a reference point.

e.g.

1kg and 2kg

2 kg could be called heavy.

2kg and 2kg

both are equivalent in weight.

so which is heavy?

It's an obvious fact that when you use comparatives like heavy, smarter, brighter, etc.

You need a reference to know which other item you are comparing it to.

But folks like deathbait, thinks otherwise.

-

aiyah Why would you want so much subsidy?

Subsidies come from tax anyway. In the end it comes back to bites us in the ass

unless they uhhh....raise the tax exclusively for the elites..

-

Originally posted by maurizio13:

Whether something is heavy or light, there needs to be a reference point.

e.g.

1kg and 2kg

2 kg could be called heavy.

2kg and 2kg

both are equivalent in weight.

so which is heavy?

It's an obvious fact that when you use comparatives like heavy, smarter, brighter, etc.

You need a reference to know which other item you are comparing it to.

But folks like deathbait, thinks otherwise.

hmm

since you want to go into the dirty details, allow me to pose a question then.

Which is a better reference point, university fees in general, or university fees only of subsidised schools?

You need work in your statistics comprehension.

By your example, there is nothing wrong with calling 2kg heavy. You may object to me calling it heavy, but the point is, "heavy" is a description. It is not a comparative term.

English phail.

You have decided to hit below the belt. I will no longer similarly restrain myself.

You have proven yourself over and over again to exercise zero logic, blindly quoting numbers without understanding what you're quoting.

You want to go into details of how the descriptive word "heavily" should be used? Let me prove once and for all how lowly educated you make yourself sound everytime you twist words for your benefit.

How do we use a descriptive? I have already shown that it is not a comparative term. A 80kg man does not go up to a 81kg man and claim he is light. No, he is lighter. And vice versa for heavy.

But a 80kg man can say he is heavy. On what basis? Because he is heavier than the average weight. We don't have a means to calculate the mean across all subsidies. But let me assure you that anything close to 50% subsidy qualifies in anyone's book as HEAVY.

To look at it another way, would you consider 40-50% discount in the store a BIG discount? Or are you going to complain that i'm misusing the word big now?

If my course were indeed in casket services, rest be assured I would already be enroute to pick you up. You spread so much hate it's a wonder lightning hasn't already struck you down.

-

maurizio13,

I agree with your observation that the term 'heavily subsidised' is subjective.

You have compared the fees in several countries. That is one way to look at it.

But to shed more light on how 'heavy' this subsidy is, perhaps you can also find exactly how much the subsidy from Govt is with regard to University education. A subsidy can be anything from 0.1% to 100%.

Contrast with healthcare, the subsidy figures have been in the papers a lot recently. Eg. C-class ward maximum subsidy is 80%.

-

I kind of agree and disagree with TS

If u study locally , its hard to get a place in UNI due to fierce competition but its cheaper and within the safety and comfort of yr family. No rent to pay

But overseas, u are most likely to be guaranteed a place in Uni , u only pay slightly more but u get a rich and diverse expereince which cant ve found in Singapore. But u will be away from yr frens and family alone most probably. and u have to pay for accomodation and food

It just a matter of personal preference

-

Local uni, they say, professors are lousy compare to that of USA or Aus. There are many FT lecturers earning cheap salaries, so sch fees must be cheap also, what heavily subsidy nonsense

-

Originally posted by t_a_s:

Local uni, they say, professors are lousy compare to that of USA or Aus. There are many FT lecturers earning cheap salaries, so sch fees must be cheap also, what heavily subsidy nonsense

i guess what u pay is what u get. i have heard negative comments about the lecturers in NTU and NUS ( though i cant confirm its true)

But in commonwealth nations , there are rules and guidelines in place that are taken seriously when it comes to workers in the education sector. They would be looked into if their standard is not up to the mark. So far, i havent seen any such policies though in place, but really enforced in the Singapore educational sector

-

Originally posted by Melbournite:

i guess what u pay is what u get. i have heard negative comments about the lecturers in NTU and NUS ( though i cant confirm its true)

But in commonwealth nations , there are rules and guidelines in place that are taken seriously when it comes to workers in the education sector. They would be looked into if their standard is not up to the mark. So far, i havent seen any such policies though in place, but really enforced in the Singapore educational sector

Do the local unis have a professor appraisal/feedback system at the end of the semester?

I know of overseas universities whereby students in the class are given an appraisal form at the end of the semester to grade the professor. It is annonymous and is submitted to the Head of the department and/or the Dean so that they can monitor the professors' conduct, teaching etc.

-

Originally posted by charlize:

Do the local unis have a professor appraisal/feedback system at the end of the semester?

I know of overseas universities whereby students in the class are given an appraisal form at the end of the semester to grade the professor. It is annonymous and is submitted to the Head of the department and/or the Dean so that they can monitor the professors' conduct, teaching etc.

none in fact...and thats pretty ironic for a developed country.

-

This was one of the issues which crept up in a conversation with my Professor during my Uni days in AUS. according to him, Singapore has a Shallow system of education both in its administrative and implementation stage which is öut of sync with whats happening around the world \d

-

How often have u heard of students in local Unis complaining about how the accent of a particular FT lecturer cant be comprehended

overseas universities carefully screen their staff if they were to apply for a professor /lecturer position if they are foreigners. And when yr accent and manner of speech is not up to the mark, then obviously the hiring commitee will give that person a straight reject as presentation skills is the most important component for a educator

Its funny how in singapore some FT lecturer with a funny acccent is still able to teach and especially at a tertiary level is shocking

-

Which Australian Uni are you talking about?

Our local Unis are really quite good by global standards.

-

Originally posted by onlooker123:

Which Australian Uni are you talking about?

Our local Unis are really quite good by global standards.

they are only good at being recognised not good in quality.

The last time i checked they were ranked 100 + globally, u call that good?!

yeah u have heard of them being top 3 in Asia and top 20 in the world but how this ranking is based and measured? Number of graduates?, complexity of studies?

what real rankings in a developed commonwealth nations does is take into account the openess and cultural diversity of the education policy of that uni. Singapore uni will fare badly in this if a ranking system were to include these in their outcome

The same reasons why warwick pulled out of Singapore

-

well, u will find this here on their official webbie dated 7 October 2006

NUS accorded World's Top 20 universities ranking

http://newshub.nus.edu.sg/headlines/0610/ranking_07oct06.htm

But look at here:

NUS drops from 19 to 33 in global rankings

http://news.asiaone.com/News/Education/Story/A1Story20071108-35284.html

THE National University of Singapore (NUS) took a tumble, from 19th spot to No. 33 this year, in the ranking of the world's top 200 universities published by The Times of London Higher Education Supplement on Thursday.

However, this is due to a new way of scoring, said QS, the careers and education group that compiled the much-followed ranking. -

may i know why the NUS website is not edited to show the recent results?

-

33rd in the world ranked by the Times of London Higher Education Supplement is still a very decent ranking.

How many Australian Unis are ranked above NUS in that ranking?

-

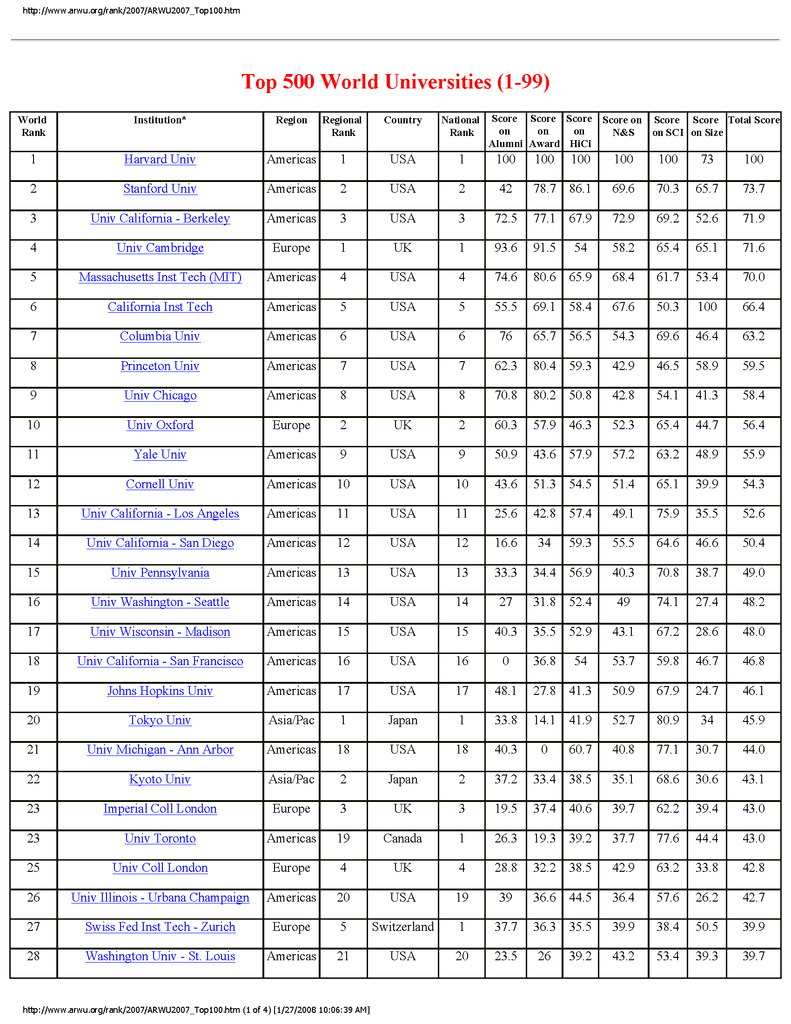

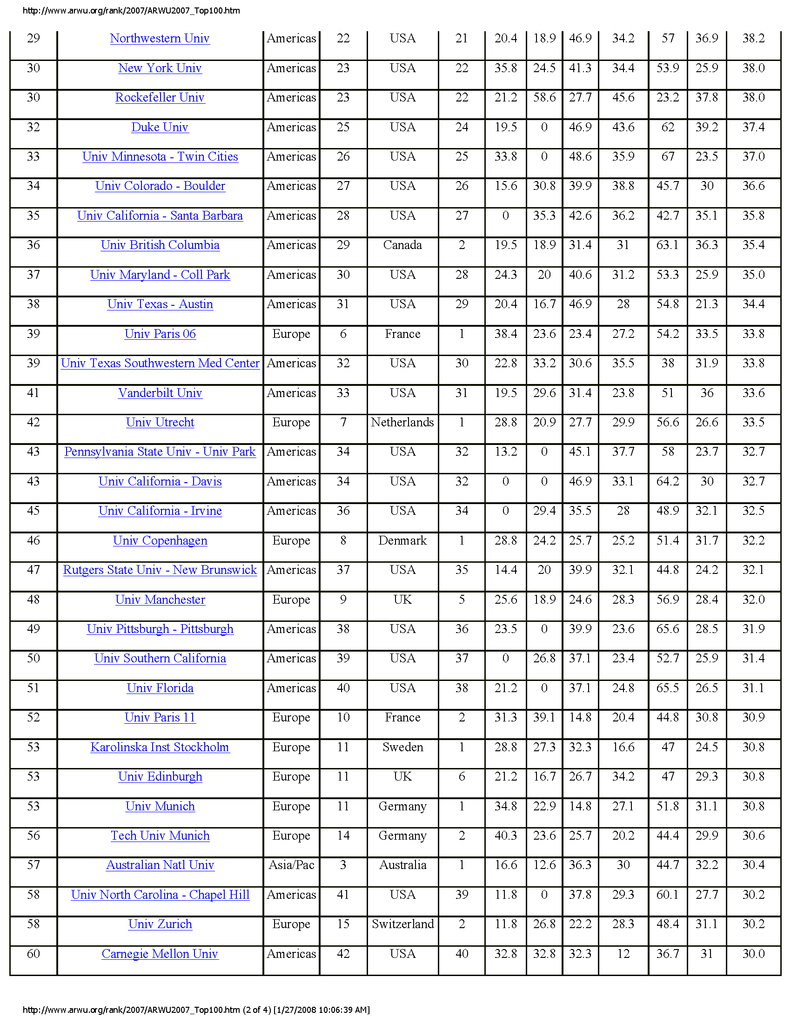

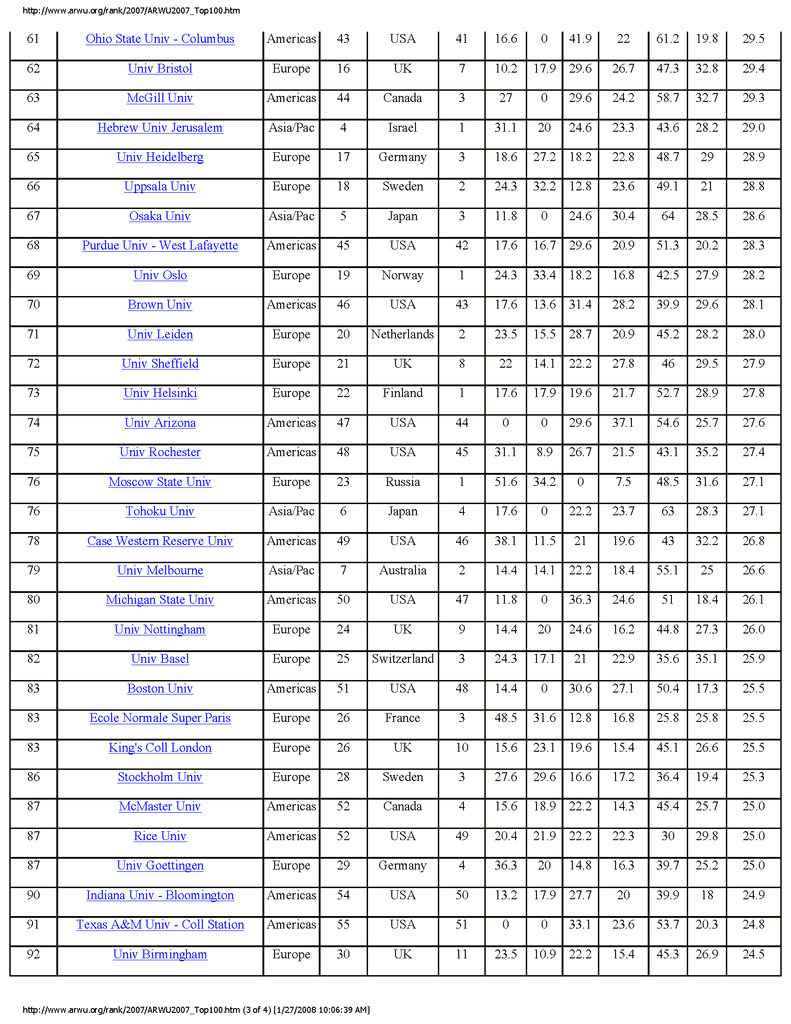

In another ranking based on academics (not on subjective reviews like Times), NUS is not even ranked in the top 100 of global universities.

If you want to understand issues, you need to look at how they analyse the data in the first place.

http://www.arwu.org/rank/2007/ARWU2007_Top100.htm

-

Times Higher Education Ranking

Methodology: What the pick of the crop means for the rest of the field

9 November 2007

We look at the top performers on each measure and suggest what their success means for the sector’s development.

The Times Higher-QS World University Rankings are a composite measure in which six criteria are added together to produce an overall table. One measure, peer review, accounts for 40 per cent of the possible score, while two others account for 20 percentage points each, with one worth 10 per cent and the other two worth 5 per cent each.

This division of possible points means it is not possible to achieve a high score in these rankings by being excellent in only one category. But it also means that two universities can obtain similar scores despite having widely differing strengths and weaknesses.

This year’s changes in the rankings methodology, mean that exceptional outlying scores on any measure no longer have a distorting effect on the whole picture. While this is to the good overall, it means that the top performers on any specific measure now tend to bunch at a score of 100 or just below. In the main tables, we show the scores for each measure to the nearest 1 per cent, but here we display one decimal place.

The most significant of our measures is academic peer review. It accounts for 40 per cent of the available score and is the most distinctive feature of our World University Rankings.

This analysis combines the opinions of 5,101 individuals, up from 1,300 in 2004, the first year of our rankings. Although Americans make up only 30 per cent of our sample, there is general agreement around the world that the US has the best universities. Berkeley and Harvard, the big two of the US system on the East and West coasts, both have a perfect score on this measure. Also prominent on this measure are Stanford, Yale, Princeton, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Los Angeles.

However, it is also apparent that academics place Oxford and Cambridge universities on roughly the same rung as their main US rivals. In addition, the effort put into staying level with its US competitors by McGill, Canada’s top institution, is seen to be paying off in terms of world esteem. (We regret that the printed Times Higher rankings supplement refers to Toronto instead of McGill in this description.)

MIT is the only specialist institution to appear in this top ten. This measure groups results in all five areas of academic life that we survey and it is hard to do well here without being visible in all or most of them. Despite its name, MIT operates in most arenas of scholarship.

This part of the rankings is the one where the rise of Asian universities is least apparent, but future years may yet see them get to the top in the opinion of fellow academics around the world.

The second of our measures, the employer review, accounts for only 10 per cent of the possible score but is of burning interest to students and their parents, as well as to universities themselves. This year, 1,471 recruiters of graduates from around the world told us where they like to get their employees. Their response suggests that graduate recruitment genuinely has become a global enterprise.

Although only 32 per cent of this sample is in Europe, these recruiters are overwhelmingly in agreement that the UK is the place to shop for graduates.

They put Cambridge and Oxford universities at the top of the list, with the London School of Economics third and the University of Manchester in fifth place. Manchester’s bid to be the north of England’s answer to Oxbridge and London already seems to be convincing employers.

Despite this British success, Harvard, MIT and Stanford are also well placed on this measure. Their appearance alongside Oxbridge and the LSE suggests that employers are a conservative breed.

The University of Melbourne emerges by some distance as Asia’s favourite institution with recruiters. It remains to be seen what recruiters will make of the novel degree system Melbourne is now introducing.

This table confirms that recruiters like big technology universities such as MIT and Imperial College London.

Two of the measures we use, peer review and citations, are qualitative and quantitative means respectively of seeing who is good at research. The two measures correlate closely. The California Institute of Technology’s highly productive research culture puts it top on citations. But this table includes some surprises, such as the appearance of the University of Alabama, although its score on other measures means that it does not appear in our main table of the world’s top 200 universities.

This table is unique in these pages for having no UK entries.

While our peer review shows that the US is the world centre for scholarly esteem, our table of international staff demonstrates beyond doubt that Europe and the Asia-Pacific region are the capitals of academic diversity. No US university appears in our top ten for overseas staff or students.

Our look at international staff contains two universities in London, the LSE and the School of Oriental and African Studies, alma maters of choice for future foreign ministers, central bankers and heads of state across the developing world. Universities in Australia, New Zealand and Switzerland also do well on this measure. But the winner in terms of overseas academics per hectare must be Hong Kong, with three universities here, including the top institution, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Perhaps even more than top staff, students have become a prized quarry for institutions around the world. For one thing, universities are free to charge them whatever the market will bear. This table shows that students agree that London is a place to spend at least part of their career, with the city claiming three of the four UK entries. The LSE is the winner among students for the second successive year, with second and third slots also going to UK institutions. Its appeal is not hard to discern. Few future economic and social scientists could resist being at a research-based elite university in the heart of one of the world’s most diverse and successful cities, close to many of the world’s top financial markets.

Second on this measure is Cranfield University, based on a rural campus north of London. Its areas of expertise include technology and business, both magnets for mobile students. Western Australia, in the shape of Curtin University of Technology, also appears in both lists, as does the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne, Switzerland, and other universities in Switzerland and France. Swiss institutions have a large nearby catchment area in France, Germany and Austria, which must make it simpler to bring in overseas students. This may allow them to resist the temptation to switch to the English-language teaching that is now sweeping Asian universities.

US universities might argue that Europe has an inbuilt advantage in this measure. Having many small countries within a short drive of each other is bound to facilitate mobility. The presence of Swiss and French universities here might support this argument, and this is one of the categories in which continental institutions excel. But Soas in London inherently draws its students from around the developing world, and Curtin and RMIT universities appear here despite Australia’s distance from other major academic centres.

Students come to university to learn, and the last of our indicators is designed to show whether the institution they arrive at will have anybody for them to learn from. It ranks universities by staff-to-student ratio.

The California Institute of Technology tops this table because it has a tiny student body coexisting with a large and active research-oriented faculty.

But the rest of the data we show suggests that anyone seeking a university where they are going to be well supplied with academic input ought to look beyond the biggest names. Yale and Imperial College London are here from among our overall top table. But so is Ulm University in Germany, despite the poor overall showing of German institutions in these pages.

This is also the only one of six top ten analyses to name a mainland Chinese university, Tsinghua in Beijing. French institutions in Lyon and Paris, which are known more for their teaching than for their research, are also in the top ten here.

Four of this table’s top ten — CalTech, Tsinghua, Cranfield and Imperial — are technology-heavy institutions. Such universities may well win out on this measure because class sizes are smaller than in areas such as the humanities.

Despite the success of Yale in this table, this measure is less kind than others to large, general universities such as Harvard and Berkeley.

Source: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=400069

-

Times Higher Education Ranking

Analysis: Fine tuning reveals distinctions

9 November 2007

Peer review is key to identifying top quality but a fairer overall picture emerges due to changes in analysis.

The extensive discussion of The Times Higher-QS World University Rankings that has taken place worldwide since their first appearance in 2004 has strengthened our belief in the general approach we have taken, and we have not made any fundamental changes to our methodology in that time.

Like the first three editions, this ranking is a composite indicator integrating peer review and opinion with quantitative data. The data-gathering for the rankings has grown in quality and quantity during their lifetime.

The core of our methodology is the belief that expert opinion is a valid way to assess the standing of top universities. Our rankings contain two strands of peer review. The more important is academic opinion, worth 40 per cent of the total score available in the rankings. The opinions are gathered, like the rest of the rankings data, by our partners QS Quacquarelli Symonds (www.topuniversities.com) which has built up a database of e-mail addresses of active academics across the world. They are invited to tell QS what area of academic life they come from, choosing from science, biomedicine, technology, social science or the arts and humanities. They are then asked to list up to 30 universities that they regard as the leaders in the academic field they know about, and in 2007 we have strengthened our measures to prevent anyone voting for his or her own institution.

This year we have the opinions of 5,101 experts, of whom 41 per cent are in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, 30 per cent in the Americas, and 29 per cent in the Asia-Pacific region. This includes respondents from 2005 and 2006 whose data have been aggregated with new responses from this year. No data more than three years old is used, and only the most recent data is taken from anyone who has responded more than once.

A further 10 per cent of the possible score in these rankings is derived from active recruiters of graduates. QS asks major global and national employers across the public and private sectors which universities they like to hire from. This year’s sample includes 1,471 people, with 43 per cent in the Americas, 32 per cent in Europe and 25 per cent in Asia-Pacific.

The first major change to this year’s rankings is in the way that these responses, and the quantitative data that makes up the rest of the table, are processed. In the past, the topmost institution on any measure has received maximum score. The others are then given a fraction of this percentage proportional to their score.

This approach has the drawback that an exceptional institution distorts the results. In 2006, our measure of citations per staff member gave the top score of 100 to the California Institute of Technology, while Harvard University, in second place, scored only 55. So almost half the variation on this measure was between the first and second-place universities.

We have solved this problem by switching from this arithmetical measure to a Z-score, which determines how far away any institution’s score is from the average. Some universities suffer as a result, such as CalTech on citations and the London School of Economics on overseas students. But this approach gives fairer results and is used by other rankings organisations.

Our quantitative measures are designed to capture key components of academic success. QS gathers the underlying data from national bodies where possible, but much of it is collected directly from universities themselves. of these measures, staff-to-student ratio is a classic gauge of an institution’s commitment to teaching. This year we have improved its rigour by obtaining full and part-time numbers for staff and students, and using full-time equivalents throughout as far as possible. This measure is worth 20 per cent of the total possible score.

A further 20 per cent of the possible score is designed to reward research excellence. Citations of an institution’s published papers by others are the accepted measure of research quality. We have used five years of citations between 2002 and 2006 as indexed by Scopus, a leading supplier of such data. Scopus (www.scopus.com) has replaced Thomson Scientific as supplier of citations data. We are confident that Scopus’s coverage is at least as thorough as Thomson’s, especially in non-English language journals. We divide the number of citations by the number of full-time equivalent staff to give an indication of the density of research firepower on each university campus.

The final part of our score is designed to measure universities’ attractiveness to staff and students. It allots five percentage points for the number of their staff who come from other countries, and a further five for their percentage of overseas students. It shows us which institutions are serious about globalisation, and points to the places where ambitious and mobile academics and students want to be.

Source: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=400068

-

Ideas without borders as excellence goes global

8 November 2007

The very top institutions may all be in the English-speaking world, but the top 200 are spread across 28 nations.

This fourth edition of The Times Higher-QS World University Rankings confirms the message of earlier editions: the top universities, on a number of measures, are in the English-speaking world. Although heavily dependent on state funding, they are independent of governments. And, in many cases, they are far from being ivory towers. Instead, they are active in generating new technology and ideas across a wide range of subject areas and are closely integrated into the economies and societies of which they form part.

Their success at generating new knowledge and producing highly employable graduates — in the US especially — has made them rich from alumni donations, research grants and spin-off companies. Harvard University, which this year is top for the fourth time, is the world’s richest by some distance, outspending the research budgets of many countries.

These rankings show the US and the UK to be home to the top universities on a wide range of measures, reflecting their success as well as the esteem in which they are held worldwide by academics and employers. Canada, Australia, Japan and Hong Kong are the only other countries to appear in the top 20, while the top Continental European institution, the Ecole Normale Supérieure, is in 26th place.

But the rankings also contain a more subversive message. The top 200 universities are in 28 countries. Four are in the developing world: in Brazil (with two entrants), Mexico and South Africa, where the University of Cape Town finally enters the top 200 after three years of near misses. Many small but affluent countries, for example Switzerland and the Scandinavian nations, have at least one entry. The story is less favourable in Mediterranean Europe. Italy and Spain muster only three universities between them in this analysis. But the overall message is that if a consistent approach to measuring academic excellence, combining academic and employer opinion with numerical data, is applied across the world, high quality can be found on every continent.

As in previous years, these rankings, whose methodology is explained more fully on page 7, rely on a comparatively small number of simple measures because of the need to gather comparable data from institutions from China to Ireland. The top few are excellent on all the criteria we use, including those that reflect research excellence, teaching quality, graduate employability and attractiveness to students.

The tables that make up these rankings differ in two important respects from the first three editions. One is that they use a new and larger database to generate citations information. The other is that the data has for the first time been processed to eliminate single outliers having a disproportionate effect on the overall result. In the past, we have allotted a top score for each measure to the highest ranked university on that criterion, and expressed all the other scores for that measure as a percentage of the figure for the highest placed institution. This meant that one exceptional university could depress the scores for 199 others. This change has had a particularly chastening effect on the London School of Economics, which has fallen from 17th place in 2006 to 59th this year.

In addition, we have strengthened our safeguards against individuals voting for their own university in the peer review part of the analysis.

These changes have had a number of effects. The adjustments in our statistical methods means substantial change in the results between 2006 and 2007, but they will also bring more stability in future years. By contrast, Harvard in pole position was the only university whose placement did not change between our 2005 and 2006 rankings.

The larger database of citations that we use this year for the first time has the effect of giving an advantage to some East Asian universities, for example Seoul National in South Korea, up to 51 from 63 last year, and Tokyo Institute of Technology, up to 90 from 118.

But we suspect that some Malaysian and Singaporean institutions have lost out because of our increased rigour over voting for one’s own university, and there are no Malaysian universities in this top 200. The two Singaporean universities we list, the National University of Singapore and Nanyang Technological University, have each taken a fall this year. The former is down from 19th last year to 33rd, while Nanyang has gone from 61st to 69th, but there is no doubt that they are both world-class universities in a country that is serious about becoming a world centre for science and technology. (That's why I say a system based on reviews by humans is subject to bias and prejudice. Whereas the ARWU system of ranking is more factual, because it's based on Research and Nobel Prizes won.)

We know these tables are used in many ways by a variety of audiences — from internationally mobile staff and students to university managers wanting a look at the international esteem in which their own and other universities are held, especially in Asia where interest in the rankings is at its highest.

A wider debate is what success in these rankings tells us about specific countries and regions. While the UK has 32 universities in the top 200, starting with Oxford, Cambridge and Imperial College London in second equal and fifth positions, Germany has only 11, starting with Heidelberg University in 60th position. This result will give more impetus to the German Government’s decision to put more research money into universities.

In a head-to-head contest between Europe and North America, Europe’s 86 listed universities easily defeat 57 in the US or even 71 for the whole of the Americas.

But a more interesting comparison may be with the Asia-Pacific region. This area musters only 41 entries in this year’s rankings. Australia’s important role in the English-speaking world and the energetic marketing of its universities across the Pacific give it 12 spots, with 11 for Japan, the world’s second-biggest economy.

But perhaps this is a rare case where quality in university rankings counts for more than quantity. Many Asian universities have higher scores in 2007 than previously. Their governments may regard this as more important than the number of appearances for their own country. The Asia-Pacific region now has five of the world’s top 30 universities, two fewer than the UK but four more than France. Some of the improvement may be due to their enhanced citations performance. But it is also very possible that these and other Asia-Pacific institutions will become yet more visible in the rankings in future years. We know that in East Asia especially, governments look at these rankings with acute interest as a measure of their national standing in the world information economy.

In the decade since the 1997 financial crisis rocked the emerging Asian economies the countries of the region have increased their state and corporate spending on higher education apace, and it will take some time for the benefits to become apparent in rankings such as these. In particular, the assumption that non-English-speaking Asia is somewhere that students come from rather than go to will not hold up indefinitely. Mobile Chinese students who would once have regarded the US or Europe as the destination of choice are now looking at universities in nearby countries.

Despite the presence of South African, Brazilian and Mexican institutions in this table, the overall message of these rankings is that the sort of universities we list here, mainly large, general institutions, with a mingling of technology specialists, are a dauntingly expensive prospect for any country, let alone one in the developing world.

There is no reason to suppose that brainpower is not distributed uniformly around the world. But it is only one of the inputs to academic excellence. It is hard to imagine a world-class university in a country that lacks a significant tax base. Even in the US and the UK, whose universities are freestanding bodies that are proud of their independent status, governments put billions of dollars and pounds into higher education and privilege it with tax breaks.

But in the modern era, even taxpayers’ money will not buy a world-class university system. The US state universities, funded mainly by state taxes and comparatively modest student fees, are not well-represented in this ranking or in national tables of US universities. With the anomalous exception of the University of California, most have fallen behind private institutions in both teaching and research. They do a competent job within the US, but have little visibility around the world.

The US and UK domination of these rankings suggests that national academic success has a number of common ingredients. The English language is a helpful start. But equally vital is the ability to connect to an economy that rewards new knowledge, for example via patents. Across the rich world, too, universities have benefited from the growing expectation that all young people with appropriate talent will go to college. This has allowed them to grow even when, as in the UK, they are not free to charge home students fees on the scale that major US universities take for granted.

The inability of Russian institutions to figure in this year’s rankings may have much to do with Moscow’s inability to put adequate funds into its higher education system. The Indian Institutes of Technology have also fallen out of the rankings this year for the first time, partly because we are now seeking opinion on each individual IIT, not on the IIT system as a whole. However, Indian institutions including the IITs, along with Russian universities, are present in our analysis of the world’s top institutions in academic areas such as technology and the sciences.

The methodology we use is designed mainly to capture excellence in multipurpose universities in the rich world. We are seeking better ways to measure higher education in developing world countries, and for ways of comparing the achievements of specialist and postgraduate institutions with those of full-spectrum universities. We welcome your input to our thinking on the future of these rankings.

Source: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=311410

-

Originally posted by Melbournite:

may i know why the NUS website is not edited to show the recent results?

I only know they sent out a mass email regarding the new ranking.