Net of Indra IS Dependent Origination?

-

I just suddenly thought of this. Could Net of Indra be a Mahayana metaphor for Dependant Origination?

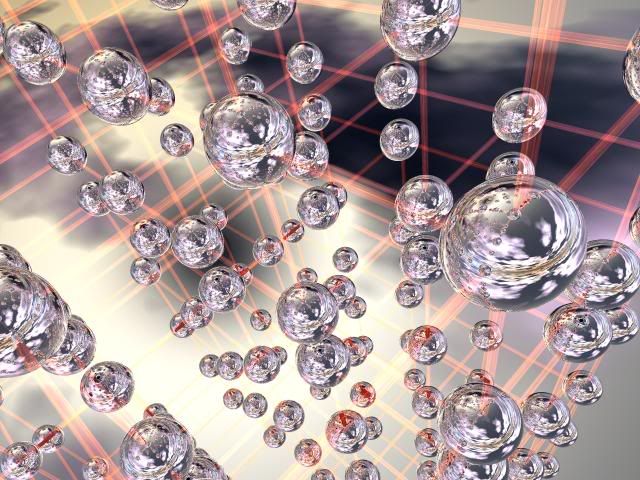

The Net of Indra: Visual Metaphor of Non-dualism & Emptiness

The metaphor of Indra's Jeweled Net is attributed to an ancient Buddhist named Tu-Shun (557-640 B.C.E.) who asks us to envision a vast net that:

* at each juncture there lies a jewel;

* each jewel reflects all the other jewels in this cosmic matrix.

* Every jewel represents an individual life form, atom, cell or unit of consciousness.

* Each jewel, in turn, is intrinsically and intimately connected to all the others;

* thus, a change in one gem is reflected in all the others.

This last aspect of the jeweled net is explored in a question/answer dialog of teacher and student in the Avatamsaka Sutra. In answer to the question: "how can all these jewels be considered one jewel?" it is replied: "If you don't believe that one jewel...is all the jewels...just put a dot on the jewel [in question]. When one jewel is dotted, there are dots on all the jewels...Since there are dots on all the jewels...We know that all the jewels are one jewel" ...".

The moral of Indra's net is that the compassionate and the constructive interventions a person makes or does can produce a ripple effect of beneficial action that will reverberate throughout the universe or until it plays out. By the same token you cannot damage one strand of the web without damaging the others or setting off a cascade effect of destruction.

Source: Awakening 101...One of the images used to illustrate the nature of reality as understood in Mahayana is The Jewel Net of Indra. According to this image, all reality is to be understood on analogy with Indra's Net. This net consists entirely of jewels. Each jewel reflects all of the other jewels, and the existence of each jewel is wholly dependent on its reflection in all of the other jewels. As such, all parts of reality are interdependent with each other, but even the most basic parts of existence have no independent existence themselves. As such, to the degree that reality takes form and appears to us, it is because the whole arises in an interdependent matrix of parts to whole and of subject to object. But in the end, there is nothing (literally no-thing) there to grasp....

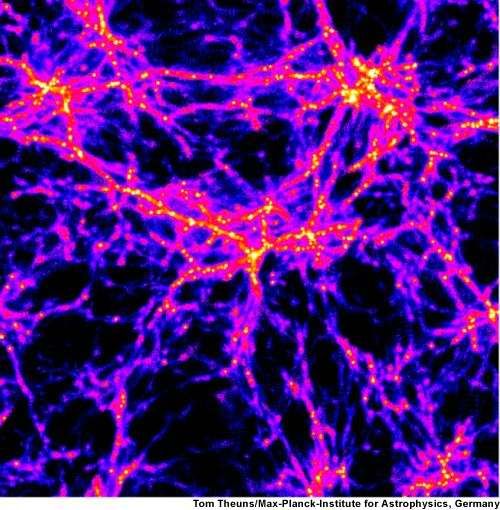

Source: Sunyata ('Emptiness')Compare the first picture with:

Computer model of early universe. Gravity arranges matter in thin filaments.

-

And dependent origination = no inherent existence = non locality, no arising, no ceasing, no etc etc (see below)

And I find this article very good By the great Master Je Tsong Khapa

By the great Master Je Tsong Khapa

http://www.buddhistinformation.com/praise_of_buddha_shakyamuni_for_.htm

By Je Tsong Khapa

Last update: December 05 2000

Résumé

· Note: "Relativity" here means "dependent origination", "not independent or absolute".

· Relativity, dependent origination, is the key to the Buddha's teaching.

· It is by directly seeing that everything is dependently originated that we can understand that everything is empty of inherent existence. And it is by seeing that everything is empty of inherent existence that we abandon all attachment or repulsion, the causes of all suffering.

· Dependent origination and emptiness are seen as in opposition, as a duality.

· But Emptiness is not in real opposition to dependent origination. One cannot exist without the other. One implies the other. They are interdependent. They are not different, not separate, but not the same.

· They are two complementary skilful means. We need both together on the path.

· Emptiness means freedom.

· All views are flawed, not absolute, empty of inherent existence.

· In Hinayana, dependent origination is taught to be a real thing, inherently existing. That is seen as in opposition to emptiness. That is why they reject emptiness.

· The things that are dependently originated do not inherently exist. The elements of dependent origination are all empty of inherent existence. The causes, effects, and the causality itself are all empty of inherent existence. That is why we say that dependent origination is also empty. All of these should be seen as illusions. It is like a flow of interdependence without anything substantial in it.

· The Middle Way it proposes is "not accepting", "not rejecting" -- away from the extremes of existence and non-existence, pointing to transcendence of all dualities

· Among all the Buddhist teachings, those of Nagarjuna and Chandrakirti are the best. They explain the best the Middle Way away from all extremes.

Praise Of Buddha Shakyamuni For His Teaching Of Relativity

Reverence to the Guru Manjughosha!

Homage to that perfect Buddha,

The Supreme Philosopher,

Who taught us relativity

Free of detruction and creation,

Without annihilation and permanence,

With no coming and no going,

Neither unity nor plurality;

The quieting of fabrications,

The ultimate beatitude!

(i.e. The eight negations describing the true nature of things -- from the Karikas introduction:

1. they do not die -- not an act of cessation -- the non-ceasing

2. and are not born, -- not an arising -- the non-arising

3. they do not cease to be -- not an interruption -- the non-annihilation

4. and are not eternal, -- not a perpetuation -- the non-permanence

5. they are not the same -- not one thing -- the non-identity

6. and are not different, -- not many things -- the non-difference

7. they do not come -- not a going forth -- the non-appearance

8. and do not go. -- not an arrival -- the non-disappearance

continued in the website.... -

"Whatever depends on conditions,

That is empty of intrinsic reality!"

What method of good instructions is there,

More marvellous than this discovery?

(i.e. Once we see the dependent origination, we do not believe in inherent existence anymore; and that is final, permanent. Everything that is dependently originated is necessarely empty of inherent existence. "Dependent origination" implies "emptiness". -- And vice versa. One cannot exist without the other. They are two interdependent concepts. They are not different or separate, but not the same.)

----

All along I knew interdependent origination but somehow I think this statement is becoming more clear to me now. -

Where is the part on non-locality?Originally posted by An Eternal Now:And dependent origination = no inherent existence = non locality, no arising, no ceasing, no etc etc (see below) -

"Why did The Buddha place such importance on Dependent Origination? What is its purpose?".

.... .......

It is becos the function of Dependent Origination is threefold:

-To explain how there can be rebirth without a soul. (Of all religions and philosophies in the world, only two,reject the theory of soul.One is Buddhism and the other is the world view of modern science.)

-To answer the question "What is life?".

-To understand why there is suffering, and where suffering comes to an end. -

Sorry its not from that website.. I added that partOriginally posted by Thusness:Where is the part on non-locality?

Non-local because nothing is caused by an agent, nothing is independant or isolated, but rather interdependently arisen like the net of indra. As such there is no 'point of origination'.

Also I think the conventional way of understanding causality as one thing causing another is also not relevant at a higher level.. am I right to say that? As causality is also empty of inherent existence...

Just remembered I posted something on this in the Holographic Universe topic I think..

http://www.heartspace.org/misc/IndraNet.html

4. Non-locality

Indra's Net shoots holes in the assumption or imputation of a solid and fixed universe 'out there'. The capacity of one jewel to reflect the light of another jewel from the other edge of infinity is something that is difficult for the linear mind, rational mind to comprehend. The fact that all nodes are simply reflections indicates that there is no particular single source point from where it all arises. -

Just found an article. This article supports that Net of Indra is the Mahayana way of understanding Dependent Origination. It seems that Mahayana is more heavy on the 'metaphysical side' of dependent origination, stressing that dependent origination is about emptiness nature.

http://www.purifymind.com/SunyataEmp.htm

Sunyata ("Emptiness"). The Mahayana tradition has put a special emphasis on sunyata. This was necessary, in part, because of the tendency among certain early Buddhist schools to assert that there were aspects of reality that were not sunya, but which had inherent in them their "own-being". Several important Buddhist philosophers dismantled these theories by arguing for the pervasiveness of sunyata in every aspect of reality. (Nagarjuna was among the most important of these.) The specific arguments are too complicated for us to deal with here. But it is important to appreciate that understanding absolutely everything as sunya could imply that even those things most revered by Buddhists (such as the arhant ideal and the rules laid down in the vinaya) were empty. Mahayanists tended to argue that members of the Hinayana traditions were attached to their ideal forms as if they were not sunya.

To some extent, sunyata is an extension of the concepts made explicit in the 3 Flaws. All things being impermanant, nothing can be seen as having an independent, lasting form of existence. And this is, in essence, what sunyata is all about. Strictly speaking, sunyata can be defined as "not svabhava". The concept svabhava means "own being", and means something like "substance" or "essence" in Western philosophy. Svabhava has to do with the notion that there is a form of being which "is" and "exists" in a form that is not dependent on context, is not subject to variation, and has a form of permanent existence. As such, the "soul" as understood in Abrahamic religions would have svabhava. God would certainly have svabhava. The Platonic forms (such as those described in the allegory of the Cave) would have svabhava.. Certain abhidharma teachings conclude that the building blocks of reality have such svabhava. But Mahayana philosophers like Nagarjuna concluded that sunyata is the fundamental characteristic of reality, and that svabhava could be found absolutely nowhere.

One of the images used to illustrate the nature of reality as understood in Mahayana is The Jewel Net of Indra. According to this image, all reality is to be understood on analogy with Indra's Net. This net consists entirely of jewels. Each jewel reflects all of the other jewels, and the existence of each jewel is wholly dependent on its reflection in all of the other jewels. As such, all parts of reality are interdependent with each other, but even the most basic parts of existence have no independent existence themselves. As such, to the degree that reality takes form and appears to us, it is because the whole arises in an interdependent matrix of parts to whole and of subject to object. But in the end, there is nothing (literally no-thing) there to grasp.

Pratitya-samutpada ("Dependent Co-arising"). The flip side of sunyata is pratitya samutpada. They are two sides of the same coin. They mean the same thing, but from two different perspectives. To the extent that sunyata is a negative concept (i.e., not svabhava), pratitya-samutpada is the positive counterpart. Pratitya-samutpada is an attempt to conceptualize the nature of the world as it appears to us, not (as with sunyata) by saying what the world is not, but by characterizing what is. I would say that pratitya-samutpada is probably just about my favorite religious-philosophical concept from within the traditions of the world. It is wonderfully subtle, and Buddhist philosophers have developed it beautifully.

As mentioned above, this concept is understood in two quite different ways in Theravada and Mahayana thought. In Theravada dependent co-arising (usually designated by its form in Pali, paticca-samuppada) is understood as a logical-causal chain which illustrates in a linear fashion the preconditions of suffering that can be analyzed and eliminated according to a strictly codified pattern of behavior. In Mahayana, on the other hand, which emphasizes the emptiness of things, dependent co-arising as a concept is used to clarify the nature of sunyata by showing that all things that appear to have independent, permanent existence are really the product of many forces interacting. Thus, in Mahayana it is stressed that all things are dependently co-arisen, because their seemingly independent existence really depends on the coming together simultaneously (the co-arising) of the various parts and forces that go into making them up. As such, pratitya-samutpada is more a metaphysical concept in Mahayana, and it is nonlinear inasmuch as it attempts to picture a universe in which all things are inextricably linked in a cosmic wholeness that cannot be unwoven into independent threads or pieces.

One illustration of sunyata and pratitya-samutpada is the Jewel Net of Indra (see above). Another is a rainbow. We know that a rainbow is real in some sense, because we can see it, locate it, measure it, and so forth. However, it is also clear that a rainbow is no "thing", but rather the product of various forces interacting as sunlight shines through an atmosphere that has water droplets in suspension. Mahayana thinkers have asserted that all phenomena, including especially individual human beings, are like this, inasmuch as it is impossible to locate any basic particle or entity that is dependent in no way for its definition and existence on the relationship that it has to other things. All things are, therefore, "empty" and "dependently co-arisen".

Many great Buddhist philosophers have thought through with great care the nature of shunyata and pratitya-samutpada. This is but a simple illustration of much more complex reasoning, such as that found in the writings of Nagarjuna, Chandrakirti, and other subtle thinkers. (See Smith, 82-112. See also Paul Ingram. 1990. "Nature's Jeweled Net: Kukai's Ecological Buddhism" on Electronic Reserve. )

It may seem that the articulation of such ideas "tends not to edification", or that it resembles absurd philosophical speculation such as "how many angels can dance on the head of a pin?" However, the study of these (and other) philosophical concepts has typically been linked with practices that train Buddhists to release themselves from attachment to or striving after "things" that might seem to offer some lasting sort of satisfaction. One of the most basic forms of attachment is the mind's tendency to grasp after objects of thought and perception as real (i.e., as having svabhava), and this tendency is reinforced in ideas that we have about the world. The use of philosophical reasoning to deconstruct such misconceptions (as they are understood within Buddhism) is a powerful vehicle for eliminating seeds that can eventually grow into very serious obstacles in one's orientation to the world.

Among the most important applications of these ideas with Mahayana has been to expose the emptiness and the co-dependently arisen qualities of even Buddhism itself. Mahayana claims itself to be an important vehicle to liberation, but it also points to its own provisional character. Mahayana does not see itself as an end, but as means to an end. That end is liberation, enlightenment, and an end to suffering. However, as with all religions, there is a tendency for the religion to reinforce itself as real, as an end in itself, within the minds of its adherents. The philosophical traditions of emptiness and dependent co-origination are important correctives to this tendency. There is an important saying within Zen: "If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him." When people come to see the Buddha as a being to be revered merely for the sake of piety itself, or when Buddhism itself becomes the chief focus of its practitioners, then it is time to "kill the Buddha", to point to the emptiness and provisional quality of Buddhism itself. -

Not bad but when studying DO or Emptiness, try not to not make it too mechanical. When we say Reality, what exactly is the Reality we are toking about? Leave out the ultimate nature of reality first.Originally posted by An Eternal Now:Just found an article. This article supports that Net of Indra is the Mahayana way of understanding Dependent Origination. It seems that Mahayana is more heavy on the 'metaphysical side' of dependent origination, stressing that dependent origination is about emptiness nature.

-

Originally posted by An Eternal Now:

What is this "it"?

4. Non-locality

Indra's Net shoots holes in the assumption or imputation of a solid and fixed universe 'out there'. The capacity of one jewel to reflect the light of another jewel from the other edge of infinity is something that is difficult for the linear mind, rational mind to comprehend. The fact that all nodes are simply reflections indicates that there is no particular single source point from where it all arises. -

Awareness?Originally posted by Thusness:Not bad but when studying DO or Emptiness, try not to not make it too mechanical. When we say Reality, what exactly is the Reality we are toking about? Leave out the ultimate nature of reality first.

-

And what has DO and Emptiness got to do with this Awareness?Originally posted by An Eternal Now:Awareness? -

its part of the webOriginally posted by Thusness:And what has DO and Emptiness got to do with this Awareness? -

-

Not sure myself... do correct me if i'm wrongOriginally posted by Thusness:And what has DO and Emptiness got to do with this Awareness?

Awareness is in the arising of phenomena which is intrinsically interconnected arising, and therefore there is no 'source' separated from the phenomena that is creating phenomena. Neither is awareness a 'source' separated from what is experienced

Rather than seeing things as separated, or awareness as separated, or a self separated from phenomena, one becomes like the net of indra itself reflecting all others and all others reflecting him, where there is no where particular which is really his 'self', or, everything is 'him' arising like the net of jewels.

Which reminds me of the Tozan article... I think they wrote something similar,

an extract from 'The Real within the Apparent'....All the myriad phenomena before his eyes-the old and the young, the honorable and the base, halls and pavilions, verandahs and corridors, plants and trees, mountains and rivers-he regards as his own original, true, and pure aspect. It is just like looking into a bright mirror and seeing his own face in it. If he continues for a long time to observe everything everywhere with this radiant insight, all appearances of themselves become the jeweled mirror of his own house, and he becomes the jeweled mirror of their houses as well. Dogen Zenji has said: "The experiencing of the manifold dharmas through using oneself is delusion; the experiencing of oneself through the coming of the manifold dharmas is Satori." This is just what I have been saying. This is the state of " mind and body discarded, discarded mind and body." It is like two mirrors mutually reflecting one another without even the shadow of an image between. Mind and the objects of mind are one and the same; things and oneself are not two. " A white horse enters the reed flowers snow is piled up in a silver bowl." This is what is known as the jeweled-mirror Samadhi...

-

Originally posted by my ex-moderator Namelessness:

I found a very interesting and significant topic here, but it's expired, so I brought it up here. It was posted by AEN: The Net of Indra: Visual Metaphor of Non-dualism & Emptiness

This is the first time I heard about it. Now I realize that the indraÂ’s net is a close metaphor of our Dharmakaya except that it didnÂ’t mention all stars(jewels) are constantly moving in the net. Thanks AEN.

I hope that scientists can take it seriously. This metaphor could be really something that would revolutionize the scientific discovery. Imaging what the discovery could do. The Dharmakaya is the energy source and projector of the Universe. If scientists know how it works, secret of life would be revealed and all religions will be united into one with science. Most importantly, in the end, no more need for this virtual Earth and reincarnation.

Well, this may be a long-shot dream. But a good one, right?

IÂ’m just thinking perhaps we could simulate how the Dharmakaya net works with 3D animation and show it to some scientists so that they could start somewhere. Of course, before we could do that, we must know it ourselves. So here is one goal for all of us who is interested in combining Buddhism and science. -

By the way, this is a related topic on scientific views and discoveries on the 'Universe as a Hologram' previously posted in the forum. Very interesting.

The Universe as a Hologram - Holographic Reality -

I think a few weeks ago I shared something Dharma Dan wrote with Thusness and he said that it is in fact the beginning of experiencing stage 6/dependent co-arising/emptiness. (Readers who have no idea what is stage 6 should read about Thusness's six stages of insights/experiences, http://buddhism.sgforums.com/?action=thread_display&thread_id=210722&page=3)

Reality can now be perceived with great breadth, precision, and clarity, and soon with no special effort. This is called “High Equanimity.” Vibrations may become predominant, and reality may become nothing but vibrations. Vibrating formless realms may even arise, with no discernable image of the body being present at all. Phenomena may even begin to lose the sense that they are of a particular sense door, and mental and physical phenomena may appear nearly indistinguishably as just vibrations of suchness, sometimes referred to as “formations.”

I put off writing about formations for a long time, as they are a conceptually difficult topic. Further, the classical definition of formations is perhaps not so clear-cut, so I wondered about imposing my own functional and experiential definitions on the term. However, as the topic of formations has arisen in so many conversations recently, I thought that it would be worth taking on despite the difficulties.

I am going to define formations as the primary experience of insight meditation when one is solidly in the fourth vipassana jhana, the 11th ñana, High Equanimity, whose formal title is actually Knowledge of Equanimity Concerning Formations. For those of you who find this circular definition completely unhelpful, formations have the following qualities when clearly experienced:

• They contain all the six sense doors in them, including thought, in a way that does not split them up sequentially in time or positionally in space. If you could take a 3D moving photograph that also captured smell, taste, touch, sound, and thought, all woven into each other seamlessly and containing a sense of flux, this would approximate the experience of one formation. From a fourth vipassana jhana point of view and from a very high dharma point of view, formations are always what occur, and if they are not clearly perceived then we experience reality the way we normally do.

• They contain not only a complete set of aspects of all six sense doors within them, but include the perception of space (volume) and even of time/movement within them.

• When the fourth vipassana jhana is first attained, subtle mental sensations might again “split off” from “this side,” much as in the way of the Knowledge of Mind and Body, but with the Three Characteristics of phenomena and the space they are a part of being breathtakingly clear. Until mental and physical sensations fully synchronize on “that side,” there can be a bit of a “tri-ality,” in which there is the sense of the observer “on this side,” and nearly the whole of body and mind as two fluxing entities “over there.” As mental phenomena and physical phenomena gradually integrate with the sense of luminous space, this experientially begs the question, “What is observing formations?” at a level that is way beyond just talking about it. For you Khabbala correspondance fans, these insights correspond to the the three points of Binah, the two points of Chockmah, and finally the single point of Kether.

• Formations are so inclusive that they viscerally demonstrate what is pointed to by the concept of “no-self” in a way that no other mode of experiencing reality can. As formations become predominant, we are faced first with the question of which side of the dualistic split we are on and then with the question of what is watching what earlier appeared to be both sides. Just keep investigating in a natural and matter-of-fact way. Let this profound dance unfold. If you have gotten to this point, you are extraordinarily close and need to do very little but relax and be gently curious about your experience.

• When experienced at very high levels of concentration, formations lose the sense that they were even formed of experiences from distinguishable sense doors. This is hard to describe, but one might try such nebulous phrases as, “waves of suchness,” or “primal, undifferentiated experience.” This is largely an artifact of experiencing formations high up in the byproducts of the fourth vipassana jhana, i.e. the first three formless realms. This aspect of how formations may be experienced is not necessary for the discussions below. -

(continued)

It is the highly inclusive quality of formations that is the most interesting, and leads to the most practical application of discussing formations. It is because they are so inclusive that they are the gateway to the Three Doors to stage 15. Fruition (see the chapter called The Three Doors). They reveal a way out of the paradox of duality, the maddening sense that “this” is observing/controlling/subject to/separated from/etc. a “that.” By containing all or nearly all of the sensations comprising one moment in a very integrated way, they contain the necessary clarity to see through the fundamental illusions.

One of the primary ways that the illusion of duality is maintained is that the mind partially “blinks out” for a part of each formation, the part it wants to section off to appear separate. In this way, there is insufficient clarity to see the interconnectedness and true nature of that part of reality, and a sense of a self is maintained. When the experience of formations arises, it comes out of a level of clarity that is so complete that this “blinking” can no longer easily occur. Thus, when formations become the dominant experience, even for short periods of time, very profound and liberating insight is close at hand. That is why there are systematic practices that train us to be very skilled in being aware of our whole mental and physical existence. The more we practice being aware of what happens, the less opportunities there are for blinking.

During the first three insight stages, we gained the ability to notice that mental and physical sensations made up our world, how they interacted, and then began to see the truth of them. We applied these skills to an object (perhaps not of our choice, but an object nonetheless), and saw it as it actually was with a high degree of clarity in the A&P. By this point, these skills in perceiving clearly have become so much of a part of who we are that they began to apply themselves to the background, space and everything that seemed to be a reference point or separate, permanent self as we entered the Dark Night. However, our objects may have been quite vague or too disconcerting to have been perceived clearly. Finally, we get to equanimity and put it all together: we can see the truth of our objects and of the whole background and are OK with this, and the result is the perception of formations.

Formations contain within them the seeming gap between this and that, as well as sensations of effort, intimacy, resistance, acceptance, and all other such aspects of sensations from which a sense of self is more easily inferred. Thus, these aspects begin to be seen in their proper place, their proper context, i.e. as an interdependent part of reality, and not split off or a self.

Further, the level of clarity out of which formations arise also allows one to see formations from the time they arise to the time they disappear, thus hitting directly at a sense of a self or sensate universe continuing coherently in time. In the first part of the path the beginning of objects was predominant. In the A&P we got a great sense of the middle of objects but missed subtle aspects of the beginning and end. In the Dark Night the endings are about all we could really perceive clearly. Formations once again put all of this work we have done together in a very natural and complete way.

Formations also explain some of the odd teachings that you might hear about “stopping thought.” There are three basic ways we might think about this dangerous ideal. We might imagine a world in which the ordinary aspects of our world which we call “thought” simply do not arise, a world of experience without those aspects of manifestation. You can get very close to this in very strong concentration states, particularly the 8th samatha jhana. We might also think of stopping experience entirely (as happens in Fruition), and this obviously includes thought.

Formations point to yet another possible interpretation of the common wish to “stop thought,” as do very high levels of realization. The seeming duality of mental and physical sensations is gone by the time we are perceiving formations well. Thoughts appear as one luminous aspect of the phenomenal world. In fact, I challenge anyone to describe the bare experience of thinking or mental sensations in terms beyond those of the five “physical” sense doors. Thus, in the face of experiencing formations, it seems crude to speak in terms of thought as separate from those of visual, tactile, auditory, gustatory, and olfactory qualities, or even to speak in terms of these being separate entities.

When perceived clearly, what we usually call “thoughts” are seen to be just aspects of the manifesting sensate world that we artificially select out and label as thought. Just as it would be odd to imagine that an ocean with many shades of blue is really many little bits of ocean, in times of high clarity it is obvious that there is manifesting reality, and it is absolutely inclusive. Look at the space between you and this book. We don’t go around selecting out little bits of space and labeling them as separate. In the face of formations, the same applies to experience, and experience obviously includes the sensations we call thought.

Page 173~175, Master the Core Teachings of the Buddha, Dharma Dan -

Wow....i missed this part. I read it a few tiems. It is really very very good. Superb!