October 23, 2011

Nagasaki is located on the southwestern tip of Kyushu which stretches relatively close to the mainland. Beginning in the 16th century the port developed rapidly as the center of trade with Portugal and China.

In 1634 the Tokugawa Shogunate, suspicious of foreigners, ordered the construction of an artificial island in Nagasaki harbor where European traders would be confined. A consortium of Nagasaki merchants paid the cost of constructing Dejima (“Exit Island”). Chinese traders were confined to a compound in the south of the city.

After a 1637 rebellion led by Nagasaki Christians the Shogunate decided to expel all Europeans. Since Dutch traders had assisted the government during the rebellion an exception was made for them. The Dutch would be allowed to send a limited number of ships every year to Dejima. The island remained an exclusively Dutch trading post until the late 1850s when the opening of Japan made it superfluous.

Today Dejima is no longer an island. “Land reclamation” projects beginning in the late 19th century have surrounded it with city streets and tall buildings. (The mountainous terrain makes it difficult for the city to expand inland.)

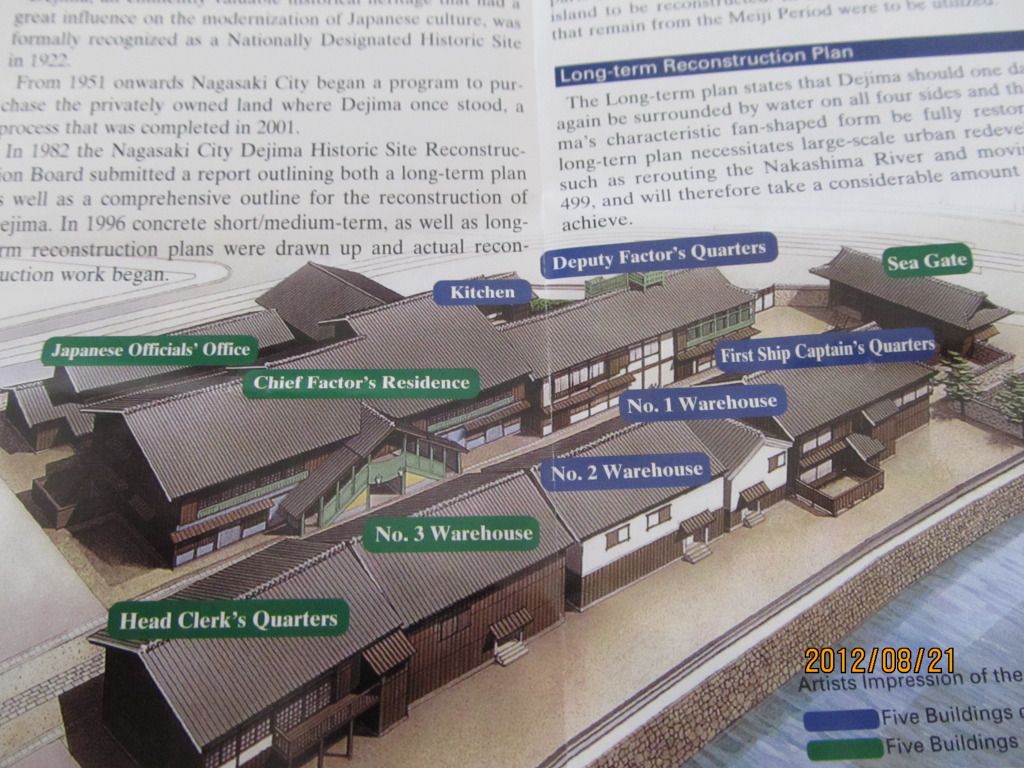

In 1996 a major project began to restore the trading post to the way it looked in the early 19th century. The project is still not complete but most of the buildings have be reconstructed and the larger ones furnished with exhibits.

This was the entrance to the island where the Dutch tradings ships would dock. The cargo would be unloaded and weighed and inventoried by Japanese customs officials.

The island had room for only one real street. Most of the buildings had living quarters on the upper level while the lower level served as warehouse space.

The building on the front left included the Captain’s Quarters. While a trading ship was docked the captain would live in an apartment on the upper level. His crew would remain confined to the ship.

About 15 employees of the Dutch East India Company lived on the island year-round. They were generally not allowed to leave the island and they were not allowed to bring their families. The only women permitted on the island were “courtesans” from the city.

The most impressive building was the home of the Opperhoofd or Chief Factor, who managed the trading post for the Dutch East India Company. It included living quarters and rooms for meetings and entertainment.

Twice a day the Dutch employees would gather at the Chief Factor’s residence for a formal meal in the main dining room.

Sometimes fancy parties were held here. This depicts a party celebrating what the Japanese called the “Dutch Winter Solstice” (i.e. Christmas.)

Warehouses on the lower levels stored the trade goods, mostly sugar from Indonesia but also silk from China and cotton from India. A small number of European manufactured goods were allowed in, mostly as gifts for the Shogun and other high officials. In exchange Japan exported silver, lacquerware, porcelain and rice.

This model shows how Dejima looked when it was a free-standing island.

For over two centuries this was the only place where Japanese and Europeans could come in contact. Japanese translators working on the island created and academic disciple called “Dutch Studies,” writing down everything they could learn about Europe. The Dutch East India Company kept a physician assigned to the island and these were a particularly useful source of information about European science and medicine.

Nagasaki Dejima Museum of History. Inside the museum the culture of Dejima during the Isolation Period, including such examples as Japan's trade with Portugal, England and Holland and the eating habits seen at the Dutch Trading House, is displayed in models and graphics.

Nagasaki Dejima Museum of History. Inside the museum the culture of Dejima during the Isolation Period, including such examples as Japan's trade with Portugal, England and Holland and the eating habits seen at the Dutch Trading House, is displayed in models and graphics.