Dear Alice,

I’m making my first trip to Japan early next year, and there are two things on my “must do in Japan” list: see Eric Clapton play at the Budokan, and eat Kobe beef. (Actually, I want to be Kobe beef, spending my life getting massages and being fed beer!) However, my former college roommate, who has lived in Japan forever, tells me that there are actually other types of Japanese beef that are just as famous and even more expensive. Really? So, what the heck are they and why haven’t I heard of them?

George T., Massachusetts,

Dear George,

This is one of those cases where perceptions outside Japan differ from perceptions within the country. In most of the world, Kobe beef is the undisputed king of meat, practically synonymous with luxurious eating. Kobe beef is also one thing everyone seems to know about Japan: I’ve got friends who couldn’t name a single Japanese prime minister, but they all know Kobe beef and will tell you at length how the “lucky” steers are pampered with classical music, beer and daily massages.

Within Japan, however, Kobe beef has competition. There are indeed other premium beef brands.

Before I name these mysterious competitors, let me explain that Japanese love to organize the best of any category into bundles of three that become known as the “Sandai,” or “Three Greats” of that type. All sorts of things get ranked, everything from mountains (the Three Greats being Mount Fuji, Mount Tate and Mount Haku) to castles (Kumamoto, Nagoya and Himeji). It’s never clear who decides these rankings, or how, yet there is surprising agreement about what constitutes the top three. And when it comes to wagyÅ« (Japanese beef), most Japanese will tell you the Three Greats are Matsuzaka beef, Kobe beef and Omi beef.

So, if there are three great beef brands in Japan today, how the heck did it happen that only Kobe beef has worldwide recognition? As far as I can tell, it was almost entirely a result of sustained word-of-mouth, dating back to the middle of the 19th century when Japan opened to the West. At that time, cattle in Japan were kept as work animals and not slaughtered for meat, so when Yokohama, for example, opened to foreign trade in 1859, foreigners found it next to impossible to put beef on their tables. Word got around that excellent cattle were raised in the western part of the country, and the foreign residents of Yokohama arranged to buy some and bring them in boat. The port closest to the cattle farms was Kobe and, pleased with the quality of the meat, foreigners in Yokohama began to refer to it as “Kobe beef.”

A few years later, in 1868, Kobe also opened to foreign trade. People poured in from all over the world and businesses were established to serve the foreign clientele. In time, a number of restaurants opened to cater to Japanese curious to try beef, which was still highly unusual in Japan. Kobe became famous forgyūnabe, a hot pot of vegetables simmered with thin slices of beef that is similar to sukiyaki.

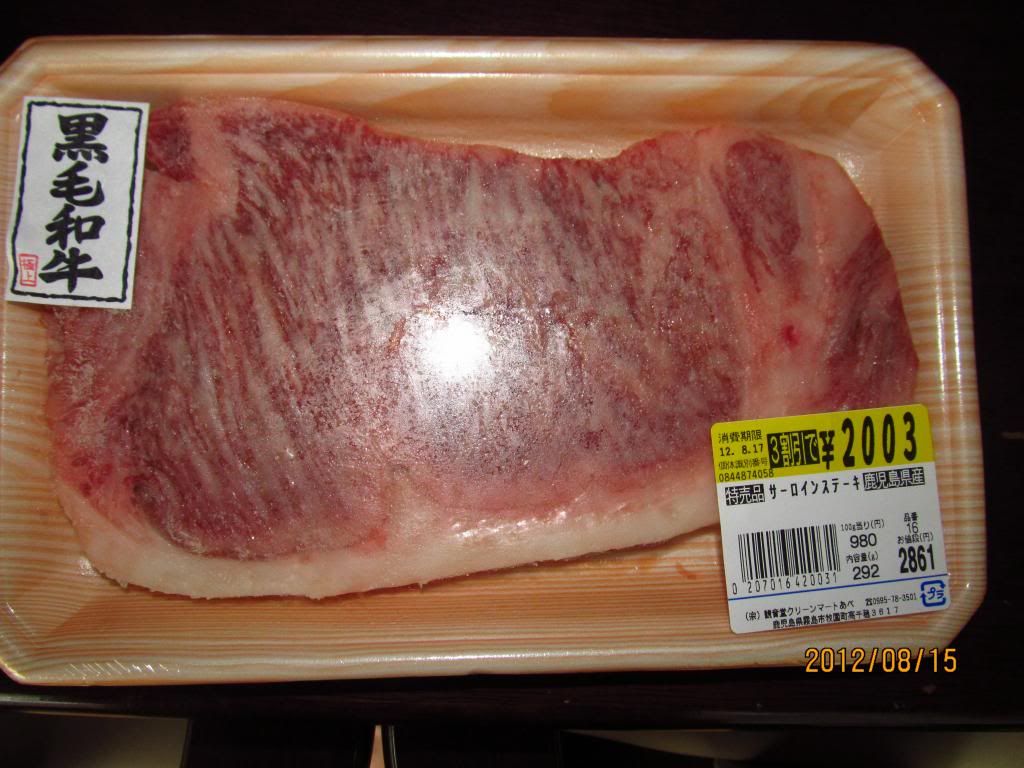

It wasn’t until 1983, when the Kobe Beef Marketing and Distribution Promotion Association was established, that a formal effort was made to manage “Kobe beef” as a brand. I called the association and spoke to an official who explained that most of the wagyÅ« cattle in Japan are a breed calledkuroge washu (Japanese Black), which includes the purebred Tajima cow that is raised for Kobe beef and other top brands of premium Japanese beef.

In order to be certified as “Kobe beef,” meat must come from a Tajima steer that was born, raised and slaughtered in Hyogo Prefecture, and must meet a set of quality standards that are the strictest in Japan. Tajima cows have fine muscle fiber and a high degree of fat marbling, which is why their meat tends to rank high in all quality factors.

Masahiko Maeda, the chef at 511 Kobe Beef Kaiseki, a Tokyo restaurant certified as serving only Kobe beef, told me the fat is of a special quality with a lower melting point than other types of beef. “That’s why the meat seems to melt in your mouth,” he said.

Approximately 7,000 head of Tajima cattle go to market every year, but only about 4,000 make the grade as Kobe beef. And while the animals do require special care, the stories about music, massage and beer are — ahem — just a bunch of bull. “We actually don’t know how those rumors started,” the official told me. “There may be a farmer who occasionally gives a cow a rub down, but neither music nor massage is standard practice and neither would affect the quality of the meat.

And the beer?

“You’ve seen the price of beer in Japan,” he quipped. “Who could afford to give that to cows?”

But seriously, beer would not make the beef taste better, and farmers don’t feed cattle beer. The association is doing its best to supplant these fables with true stories, such as how breeders have meticulously maintained the pure Tajima bloodline for hundreds of years in order to protect and preserve the special taste of Kobe beef. As part of that effort, they’ve launched a swanky website with English and Chinese as well as Japanese.

True Kobe beef is scarce, accounting for just 0.06 percent of the Japanese beef market. Not surprisingly, very little is exported, but when Kobe beef does leave the country, full details are posted on the association’s website so anyone can verify that it’s certified. I looked recently and saw small shipments only to Macau, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand and the United States, where the meat is sold in authorized shops and restaurants.

So, what to do if you live somewhere else but have a hankering for real Kobe beef? You’ll just have to visit Japan. If you time it right, you can see Eric Clapton too.

We recently paid a visit to the farm of Kagoshima Kuro-Ushi (or black cows), one of the top brands in Japan out of all those based on pedigree or location.

We recently paid a visit to the farm of Kagoshima Kuro-Ushi (or black cows), one of the top brands in Japan out of all those based on pedigree or location.

JA Zen-Noh Nagasaki Livestock Livestock Division section Nagasaki Dejima-machi 1-20 TEL 095-820-2184 FAX 095-823-7840

JA Zen-Noh Nagasaki Livestock Livestock Division section Nagasaki Dejima-machi 1-20 TEL 095-820-2184 FAX 095-823-7840

Hakata Wagyu cattle is produced by the registered

Hakata Wagyu cattle is produced by the registered

The Japanese Black was primarily used as the “workhorse” prior to the turn of the 20th Century. This breed was improved during the Meiji Era through crossbreeding with foreign breeds, and was certified as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1944. It is raised in most Prefectures of Japan, and more than 90% of Wagyu raised and fattened in Japan is of this breed. Fine strips of fat are found even in its lean meat (known as marbling). The flavor of the fat is exquisite, with a buttery, tender texture that dissolves in one’s mouth. Slaughter age is around 28-30month with an average Japanese grade of BMS 5.6

The Japanese Black was primarily used as the “workhorse” prior to the turn of the 20th Century. This breed was improved during the Meiji Era through crossbreeding with foreign breeds, and was certified as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1944. It is raised in most Prefectures of Japan, and more than 90% of Wagyu raised and fattened in Japan is of this breed. Fine strips of fat are found even in its lean meat (known as marbling). The flavor of the fat is exquisite, with a buttery, tender texture that dissolves in one’s mouth. Slaughter age is around 28-30month with an average Japanese grade of BMS 5.6 Also known as “Akaushi (Aka =red ushi =cattle),” the Japanese Brown is raised primarily in Kumamoto and Kochi Prefectures. The Kumamoto line is the most common with several hundred thousand in existence. The Kochi line has less than two thousand in existence and is only found in Japan. They can be distinguish by the dark points on its nose and feet. The more dominant Kumamoto line was improved by crossbreeding Simmental with Hanwoo(Korean Red), which was formerly used as a “work horse” during the Meiji Era. It was certified as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1944. Among its characteristics is its low fat content, about 12% or less. Because it contains much lean meat, its tastiness and pleasantly firm texture is highly enjoyable. Its fat is also not very heavy but is of fine texture, and has been attracting a great deal of attention by way of its healthiness and mild taste. Slaughter age is around 25 months and this is attributed to the lower level of marbling averaging a Japanese Grade of BMS 3.2

Also known as “Akaushi (Aka =red ushi =cattle),” the Japanese Brown is raised primarily in Kumamoto and Kochi Prefectures. The Kumamoto line is the most common with several hundred thousand in existence. The Kochi line has less than two thousand in existence and is only found in Japan. They can be distinguish by the dark points on its nose and feet. The more dominant Kumamoto line was improved by crossbreeding Simmental with Hanwoo(Korean Red), which was formerly used as a “work horse” during the Meiji Era. It was certified as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1944. Among its characteristics is its low fat content, about 12% or less. Because it contains much lean meat, its tastiness and pleasantly firm texture is highly enjoyable. Its fat is also not very heavy but is of fine texture, and has been attracting a great deal of attention by way of its healthiness and mild taste. Slaughter age is around 25 months and this is attributed to the lower level of marbling averaging a Japanese Grade of BMS 3.2.jpeg) The Japanese Shorthorn is raised mainly in the Tohoku Region. This breed was improved by crossbreeding the Shorthorn with the indigenous Nanbu Cattle. It has been continuously improved thereafter, until its certification as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1957. Its meat contains much lean meat and low fat content, and has a mild and savory flavor. It also contains inosinic acid (an compound important in metabolism) and glutamic acid, which are substances that enhance flavor and protein builder. The Japanese grade is BMS 3 or below but it is favored by many for its “different” taste.

The Japanese Shorthorn is raised mainly in the Tohoku Region. This breed was improved by crossbreeding the Shorthorn with the indigenous Nanbu Cattle. It has been continuously improved thereafter, until its certification as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1957. Its meat contains much lean meat and low fat content, and has a mild and savory flavor. It also contains inosinic acid (an compound important in metabolism) and glutamic acid, which are substances that enhance flavor and protein builder. The Japanese grade is BMS 3 or below but it is favored by many for its “different” taste. The Japanese Polled was produced through crossbreeding of Aberdeen Angus imported from Scotland with the indigenous Japanese Black in 1920. It was further improved thereafter, and was certified as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1944. Its characteristics include its high lean meat content and distinctive Wagyu taste. It contains a high percentage of amino acid and has a rich chewy, meaty flavor. The current population of Japanese Polled is the smallest of all four(4) breeds with only several hundred remain in existence today.

The Japanese Polled was produced through crossbreeding of Aberdeen Angus imported from Scotland with the indigenous Japanese Black in 1920. It was further improved thereafter, and was certified as indigenous Japanese beef cattle in 1944. Its characteristics include its high lean meat content and distinctive Wagyu taste. It contains a high percentage of amino acid and has a rich chewy, meaty flavor. The current population of Japanese Polled is the smallest of all four(4) breeds with only several hundred remain in existence today.

Kagoshima, the prefecture, is home to one of the largest livestock industries in Japan and most gourmands are familiar with the Berkshire-style pork that comes from the region. However, Kagoshima actually produces the highest quantity of beef that comes out of Japan, with almost 20% of Japanese wagyu originating here. Thanks to the temperate climate and the Japanese black cattle breed, the meat that comes from Kagoshima is known for its tenderness as well as its well-balanced marbling. Kagoshima beef is the preferred beef at Robuchon a Galera in Macau, where Le Boeuf Kagoshima is a signature dish. Executive chef Francky Semblat grills the sirloin part of the beef to give it a light smoked flavour that complements the grey shallot garnish, while also preserving the integrity of the meat's flavour.

Kagoshima, the prefecture, is home to one of the largest livestock industries in Japan and most gourmands are familiar with the Berkshire-style pork that comes from the region. However, Kagoshima actually produces the highest quantity of beef that comes out of Japan, with almost 20% of Japanese wagyu originating here. Thanks to the temperate climate and the Japanese black cattle breed, the meat that comes from Kagoshima is known for its tenderness as well as its well-balanced marbling. Kagoshima beef is the preferred beef at Robuchon a Galera in Macau, where Le Boeuf Kagoshima is a signature dish. Executive chef Francky Semblat grills the sirloin part of the beef to give it a light smoked flavour that complements the grey shallot garnish, while also preserving the integrity of the meat's flavour.  Kumamoto may lead most people think of oysters, but the Kumamoto red wagyu cattle from the southern island of Kyushu are actually the only free-grazing cattle in all of Japan. The 60-000 head herd are known for an intense buttery flavour, extreme tenderness and enhanced marbling. They also have a higher percentage of monounsaturated fat than any other breed. The Kowloon Shangri-La has recently teamed up with Kumamoto prefecture's government. Chef Peter Ng at Shang Palace uses A5 Kumamoto black wagyu to create some interesting Chinese dishes such as boiled wagyu beef dumplings with pomelo peel and chicken broth. Purists will be amazed at the perfect simplicty of the stir-fried diced wagyu beef with plain sliced Kumamoto tomatoes.

Kumamoto may lead most people think of oysters, but the Kumamoto red wagyu cattle from the southern island of Kyushu are actually the only free-grazing cattle in all of Japan. The 60-000 head herd are known for an intense buttery flavour, extreme tenderness and enhanced marbling. They also have a higher percentage of monounsaturated fat than any other breed. The Kowloon Shangri-La has recently teamed up with Kumamoto prefecture's government. Chef Peter Ng at Shang Palace uses A5 Kumamoto black wagyu to create some interesting Chinese dishes such as boiled wagyu beef dumplings with pomelo peel and chicken broth. Purists will be amazed at the perfect simplicty of the stir-fried diced wagyu beef with plain sliced Kumamoto tomatoes. Saga is located on the northwest part of Kyushu island, and beef from Saga is considered one of the big three in Japan, along with Kobe and Matsuzaka. According to executive chef Erik Idos from Nobu, the prefecture uses a special calf-rearing technology, ensuring that the cow suffers no stress at all. Unlike Matsuzaka beef, Saga beef is widely available here. If you want to try Saga beef in all its glory, Nobu at the InterContinental serves the beef in both traditional and modern ways. The traditional Japanese methods include cooking A5 Saga beef on a toban yaki (a ceramic plate) or as tataki; or you could try more innovative dishes such as a beef truffle nigiri sushi or even beef tacos.

Saga is located on the northwest part of Kyushu island, and beef from Saga is considered one of the big three in Japan, along with Kobe and Matsuzaka. According to executive chef Erik Idos from Nobu, the prefecture uses a special calf-rearing technology, ensuring that the cow suffers no stress at all. Unlike Matsuzaka beef, Saga beef is widely available here. If you want to try Saga beef in all its glory, Nobu at the InterContinental serves the beef in both traditional and modern ways. The traditional Japanese methods include cooking A5 Saga beef on a toban yaki (a ceramic plate) or as tataki; or you could try more innovative dishes such as a beef truffle nigiri sushi or even beef tacos. Sommelier Terence Wong recommends either the toban yaki with a Spanish or Italian red to match the richness of the dish, or Nobu's own private label Daiginio TK40 sake.

Sommelier Terence Wong recommends either the toban yaki with a Spanish or Italian red to match the richness of the dish, or Nobu's own private label Daiginio TK40 sake.

Beefing up: These are all purebred Tajima steers raised in Hyogo Prefecture but only the best of them will make the grade as certified 'Kobe beef,' a delicacy known for its fine texture and delicious taste.

Beefing up: These are all purebred Tajima steers raised in Hyogo Prefecture but only the best of them will make the grade as certified 'Kobe beef,' a delicacy known for its fine texture and delicious taste.