|

By Vaudine England

BBC News, Hong Kong

|

Five Chinese vessels surrounded the USNS Impeccable on 8 March

|

When Dutch ships sailed up the River Thames into London in 1688, it was clear they were an invading force.

The freedom of the seas was a well-established idea in the 17th Century, with states only able to claim a narrow belt of sea around their own coast.

But as the United States and China have discovered in recent days, that certainty is much harder to come by now.

Tensions were raised after an unarmed US navy surveillance vessel was jostled by five Chinese ships in the South China Sea last weekend.

The Pentagon accused the Chinese vessels of "harassment" during the routine operations in international waters.

Beijing says the US ship behaved "like a spy" and accused it of breaking international law by operating in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The debate over a nation's claim to marine territory has been turbulent - after all, the seas carry immense riches of fish, oil, gas and other resources, as well strategic navigation rights.

Law of the sea

Central to all efforts to disentangling such claims is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea - created in 1982 after years of international negotiations.

This is, in effect, a constitution governing the oceans - granting not just the EEZs, but right of access to the sea for land-locked states, the right to conduct marine research, mandating control of resources on the seabed, and creating an international tribunal to settle conflicts.

|

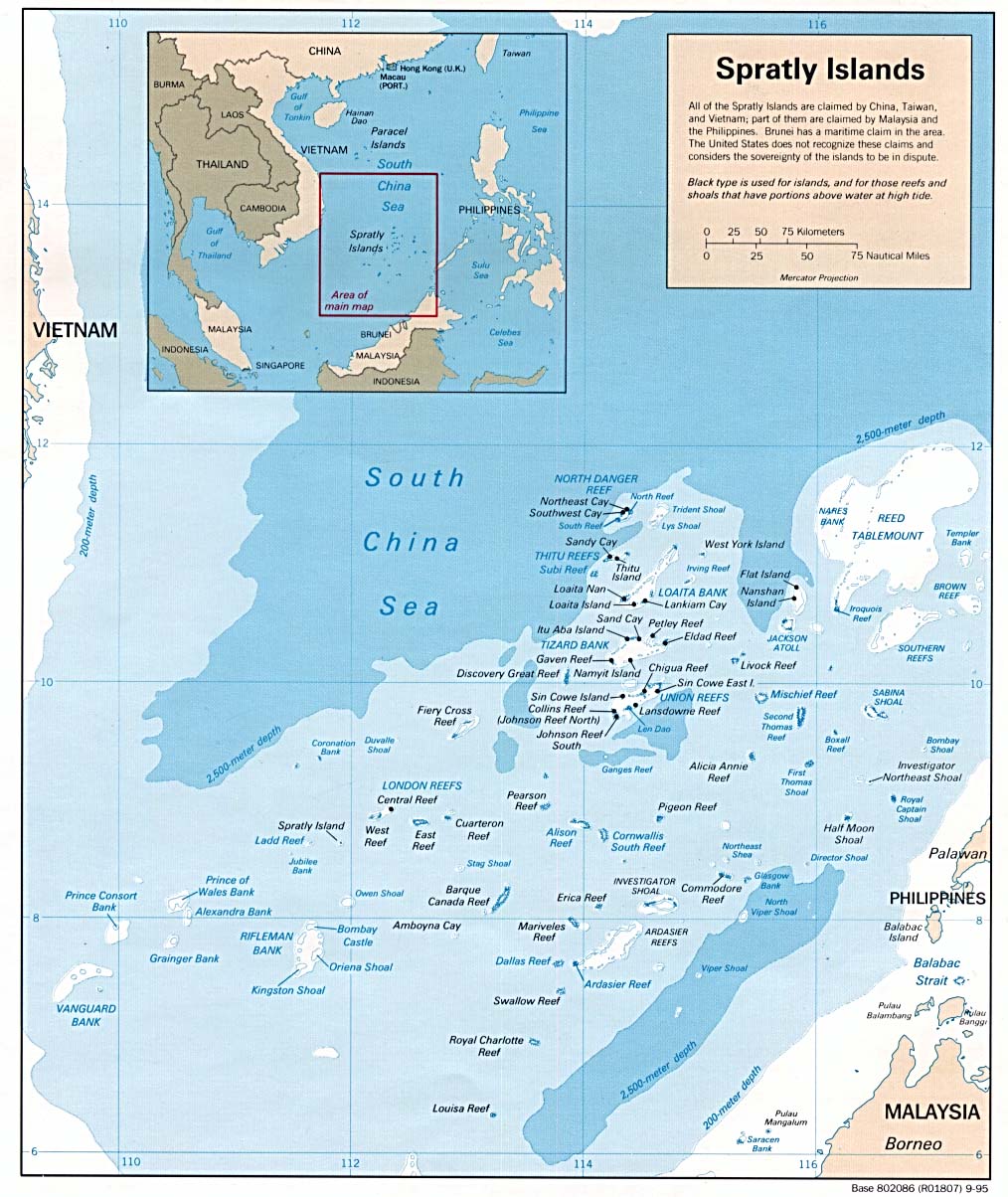

SOUTH CHINA SEA TENSIONS

Territorial claims from China, the Philippines, Taiwan, Brunei, Vietnam and Malaysia overlap in resource-rich sea

Hosts some of the world's busiest shipping lanes

China says the US was in its Exclusive Economic Zone - but the two sides disagree on what activities are allowed in an EEZ

|

So could the US-China spat, south of Hainan in the South China Sea, simply be put to the UN tribunal and solved?

Unfortunately, it is not that simple.

Unlike China, the US has signed the UN Convention, but has not ratified it.

This means it has promised not to undertake any action that might defeat the Convention's goals, but it does not consent to be legally bound by its provisions.

"This puts the US in an awkward position," said Dr Mark J Valencia, a leading maritime expert. "They are trying to interpret the terms of the Convention in their favour, which they are not a party to."

The Law of the Sea provides for EEZs - sea zones generally extending 200 nautical miles (370km) from a nation's coast, giving it special rights over the exploration and use of marine resources. This is complicated where EEZs overlap.

Without seeing detailed maps of exactly where the US ship was when confronted by the Chinese, experts have been hesitant to say exactly who was right.

If the USNS Impeccable was in China's EEZ, it could have been there perfectly legally - depending on what it was doing.

China says the US was "spying", and thus conducting activities that could be seen as preparation for conflict.

'Eye of the beholder'

So, does China have the moral superiority in this row?

Again, it is not that simple.

"China also conducts intelligence operations in what the Japanese claim as their EEZ," noted Dr Jurgen Haacke of the London School of Economics.

According to the UN Law of the Sea, intelligence operations are normally not deemed "innocent" if they occur in territorial waters.

"Some might argue that intelligence gathering should not be considered to amount to peaceful activity if it was conducted in the EEZ. Whether it is may be in the eye of the beholder," says Dr Haacke.

Dr Valencia agrees.

The Japan-China argument centres on the Diaoyu islands (known in Japan as the Senkaku) and, in law, refers to an area of still-disputed sovereignty.

"China has done things in Japan which it has accused the US of," noted Dr Valencia.

These actions include infringements of the Law of the Sea, such as having a submarine submerged instead of obvious on the surface, or sailing intelligence-gathering ships around in other nations' waters.

Jockeying for position

This is where maps defined by law distort into maps defined by the larger political realities - where geography becomes geopolitics.

The US has long had the seas around Asia to themselves, able to extend their considerable (often nuclear-powered) naval power in and out of Asian states' waters.

Mr Obama has tried to resolve the dispute in talks with Chinese officials

|

Depending what they do there, many of these states have no problem with that.

But China is not alone in its irritation at the assumption of freedom across the high seas.

Indonesia, a key player in talks shaping the Law of the Sea, has been irritated by the US navy sailing ships through its straits at will.

So too has Vietnam, which has also protested against Chinese military exercises in its waters.

But only China has made its irritation so public.

Analysts say voluntary codes of conduct across Asia's seas need to be strengthened into enforceable guidelines to avoid future conflicts.

Underlying the recent US-China spat is a fear in some South East Asian states, as well as in the West, of China's growing military might.

"While there may even be some sympathy for China's robust actions given more widespread concerns about how the US collects intelligence, China challenging the US creates instability and is therefore generally not in the interest of other Asian countries," says Dr Haacke.

China has protested before - when a Chinese frigate confronted the USNS Bowitch in the Yellow Sea in March 2001.

The next month, a Chinese jet fighter collided with a US surveillance plane over Hainan, rupturing US-China defence contacts for a while.

Neither the US nor China can claim to be wholly right. "It's not a slam dunk on either side," says Dr Valencia.

There is a jockeying for position afoot across Asia's rich and contested seas. So long as the US refuses to ratify the UN Convention "it's going to get worse", he says.

|